Different Mediums, Same Thinking.

What shifted for me when I moved from fashion to home and started learning User Experience (UX) design

Insights

December 30, 2025

For most of my career, I thought my job was to design things. In fashion, that meant garments. In home, it meant products meant to live in real spaces. I focused on fabric, color, pattern, form, finish, and whether something felt right. If it looked good, fit well, shipped on time, and stayed on budget, it felt like a win.

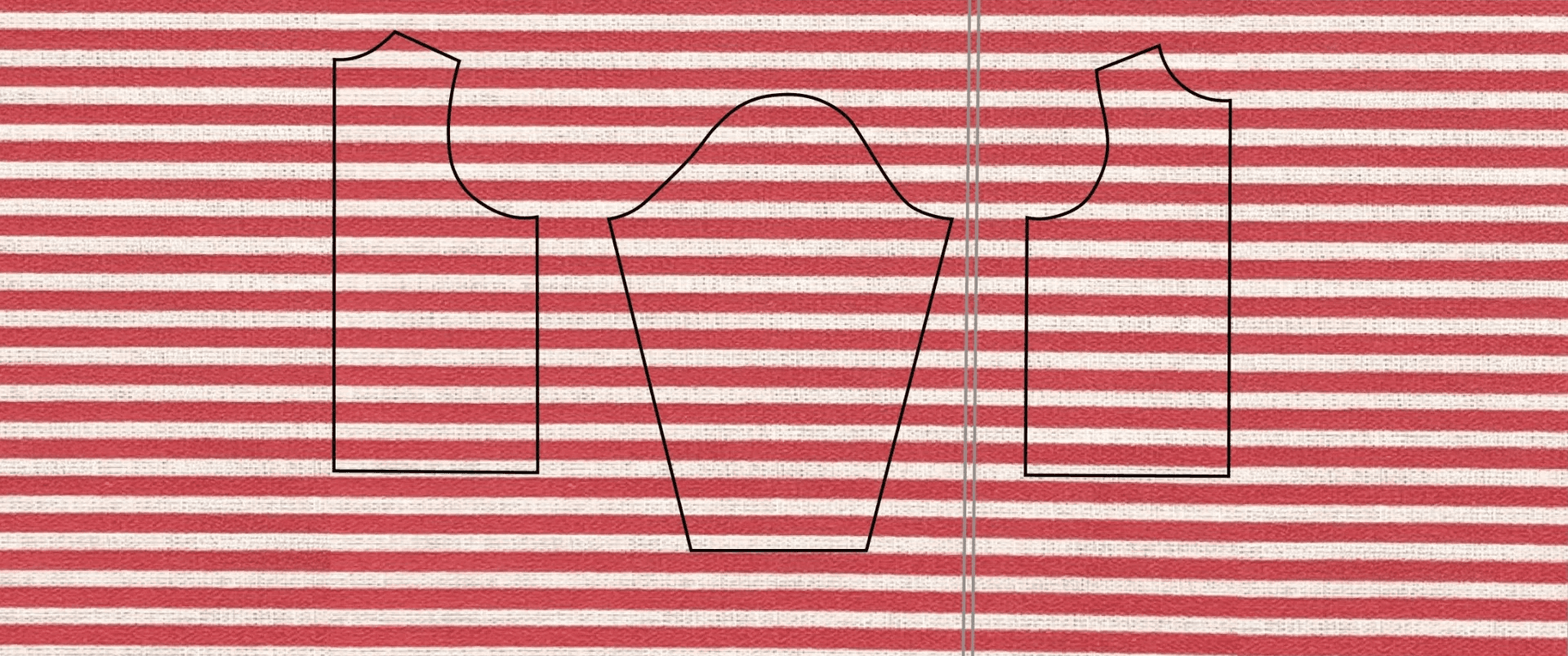

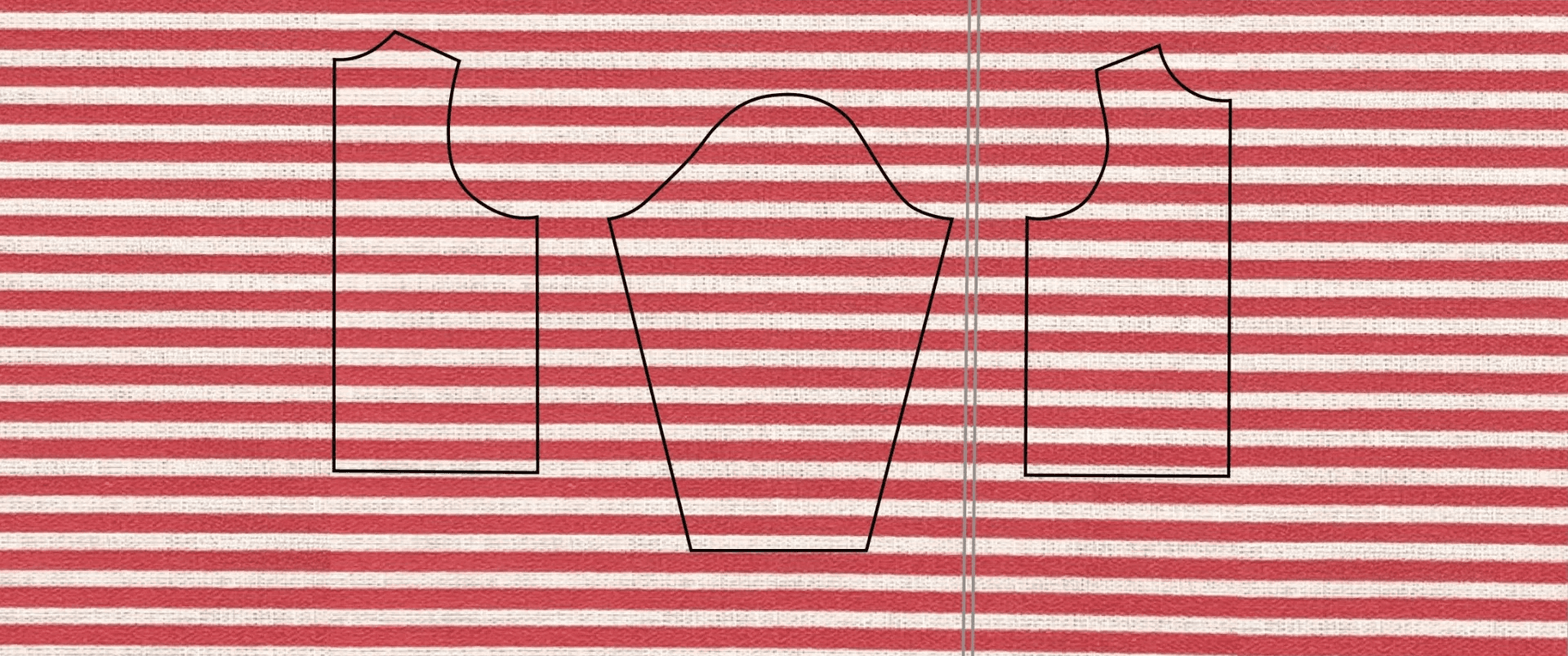

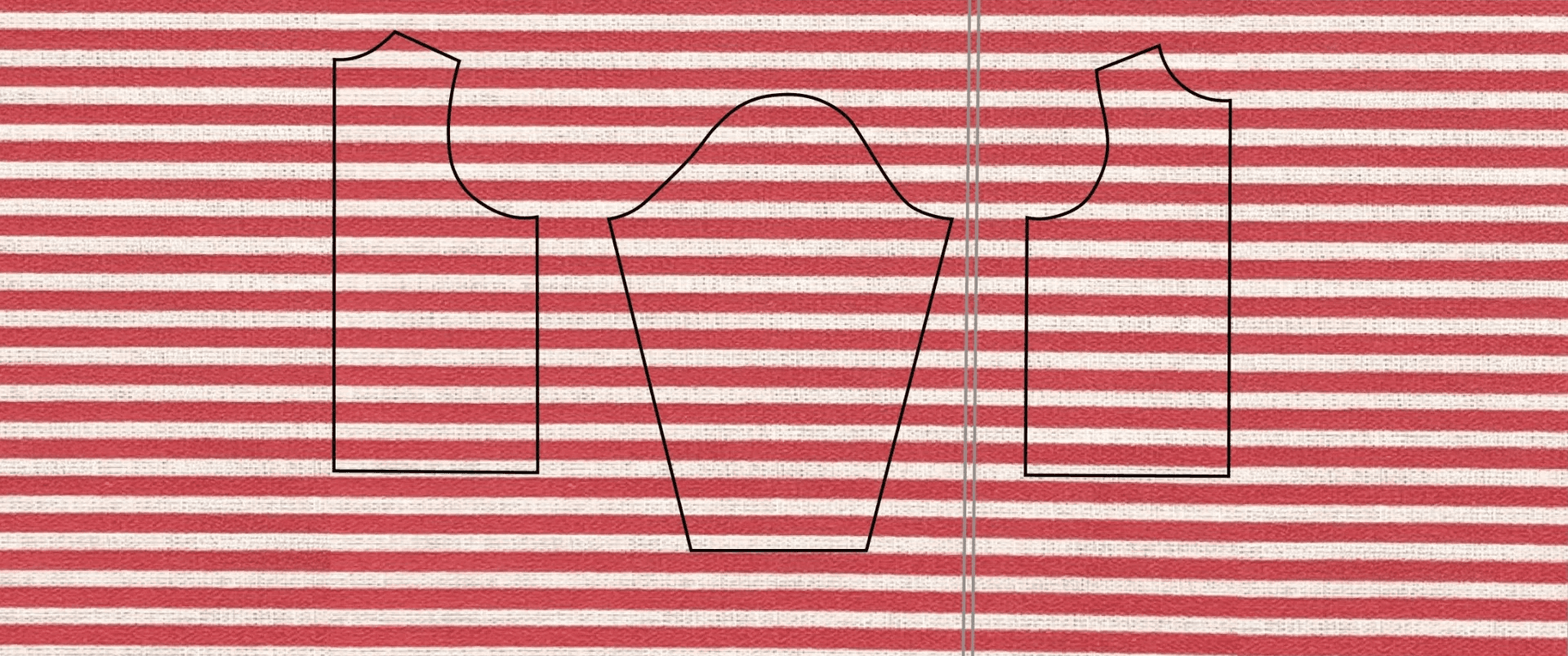

What I didn’t fully appreciate at the time was how many trade-offs were baked into every decision. A shirt stripe that needed to match at the side seams meant higher yield and higher cost. A curve added to a pocket design meant slower production. You never got everything. You chose what mattered most and accepted what you had to give up.

When I moved into home, that reality got even louder. Lead times stretched and commitments got heavier. A window treatment isn’t seasonal. It has to live for years. You learn quickly that a “great idea” isn’t enough. It has to survive manufacturing, logistics, and how people actually live with it.

Starting the Springboard UX bootcamp didn’t feel like learning a completely new way of thinking. It felt more like learning a new language for something I already understood. UX isn’t about screens; it’s about designing systems that work when people are distracted, rushed, or unsure.

In fashion, you don’t design a sample. You design something that has to scale across sizes, costs, and factories. In UX, you don’t design a screen; you design something that has to scale across users, devices, and edge cases you can’t fully predict. The trade-offs are still there, but they show up differently.

What changed for me wasn’t the discipline. It was the lens through which I designed. In physical product design, use is constrained by reality. A garment or a window treatment only works one way. You design knowing how it will be worn or installed because it cannot function otherwise. Try putting pants on upside down and the product fails immediately.

In UX, the product doesn’t enforce use in the same way. People click out of order. They skip steps. They bring assumptions you didn’t design for. The work becomes less about defining a single correct path and more about guiding behavior without spelling it out.

I stopped focusing on whether a design worked as intended and started focusing on how it behaved when people used it differently than I expected. That shift has followed me from fashion to home and now into UX.

Different mediums. Same thinking.

More to Discover

Different Mediums, Same Thinking.

What shifted for me when I moved from fashion to home and started learning User Experience (UX) design

Insights

December 30, 2025

For most of my career, I thought my job was to design things. In fashion, that meant garments. In home, it meant products meant to live in real spaces. I focused on fabric, color, pattern, form, finish, and whether something felt right. If it looked good, fit well, shipped on time, and stayed on budget, it felt like a win.

What I didn’t fully appreciate at the time was how many trade-offs were baked into every decision. A shirt stripe that needed to match at the side seams meant higher yield and higher cost. A curve added to a pocket design meant slower production. You never got everything. You chose what mattered most and accepted what you had to give up.

When I moved into home, that reality got even louder. Lead times stretched and commitments got heavier. A window treatment isn’t seasonal. It has to live for years. You learn quickly that a “great idea” isn’t enough. It has to survive manufacturing, logistics, and how people actually live with it.

Starting the Springboard UX bootcamp didn’t feel like learning a completely new way of thinking. It felt more like learning a new language for something I already understood. UX isn’t about screens; it’s about designing systems that work when people are distracted, rushed, or unsure.

In fashion, you don’t design a sample. You design something that has to scale across sizes, costs, and factories. In UX, you don’t design a screen; you design something that has to scale across users, devices, and edge cases you can’t fully predict. The trade-offs are still there, but they show up differently.

What changed for me wasn’t the discipline. It was the lens through which I designed. In physical product design, use is constrained by reality. A garment or a window treatment only works one way. You design knowing how it will be worn or installed because it cannot function otherwise. Try putting pants on upside down and the product fails immediately.

In UX, the product doesn’t enforce use in the same way. People click out of order. They skip steps. They bring assumptions you didn’t design for. The work becomes less about defining a single correct path and more about guiding behavior without spelling it out.

I stopped focusing on whether a design worked as intended and started focusing on how it behaved when people used it differently than I expected. That shift has followed me from fashion to home and now into UX.

Different mediums. Same thinking.

More to Discover

Different Mediums, Same Thinking.

What shifted for me when I moved from fashion to home and started learning User Experience (UX) design

Insights

December 30, 2025

For most of my career, I thought my job was to design things. In fashion, that meant garments. In home, it meant products meant to live in real spaces. I focused on fabric, color, pattern, form, finish, and whether something felt right. If it looked good, fit well, shipped on time, and stayed on budget, it felt like a win.

What I didn’t fully appreciate at the time was how many trade-offs were baked into every decision. A shirt stripe that needed to match at the side seams meant higher yield and higher cost. A curve added to a pocket design meant slower production. You never got everything. You chose what mattered most and accepted what you had to give up.

When I moved into home, that reality got even louder. Lead times stretched and commitments got heavier. A window treatment isn’t seasonal. It has to live for years. You learn quickly that a “great idea” isn’t enough. It has to survive manufacturing, logistics, and how people actually live with it.

Starting the Springboard UX bootcamp didn’t feel like learning a completely new way of thinking. It felt more like learning a new language for something I already understood. UX isn’t about screens; it’s about designing systems that work when people are distracted, rushed, or unsure.

In fashion, you don’t design a sample. You design something that has to scale across sizes, costs, and factories. In UX, you don’t design a screen; you design something that has to scale across users, devices, and edge cases you can’t fully predict. The trade-offs are still there, but they show up differently.

What changed for me wasn’t the discipline. It was the lens through which I designed. In physical product design, use is constrained by reality. A garment or a window treatment only works one way. You design knowing how it will be worn or installed because it cannot function otherwise. Try putting pants on upside down and the product fails immediately.

In UX, the product doesn’t enforce use in the same way. People click out of order. They skip steps. They bring assumptions you didn’t design for. The work becomes less about defining a single correct path and more about guiding behavior without spelling it out.

I stopped focusing on whether a design worked as intended and started focusing on how it behaved when people used it differently than I expected. That shift has followed me from fashion to home and now into UX.

Different mediums. Same thinking.